Figure 1: My Sister and I. Photo Credit NLL

Mathew Knowles, father of U.S. pop stars Beyoncé and Solange was recently in the media discussing his own struggles with colorism as the reason for marrying the girls’ mother Tina. Daddy Knowles further posited that Beyoncé would not be as successful if she were dark-skinned. Black Twitter erupted on opposing sides of the coin. Many tweets agreed with his assertions and purported that colorism is a lingering issue, while others disagreed about Beyonce’s success as a direct correlation to her skin tone and named many dark-skinned entertainers who are successful. Simultaneously, on the Social Media forum of passionate discourses is a dialogue about young biracial actress – Amandla Stenberg who discontinued her pursuit of a possible role in the Black Panther movie, because of her skin color. She felt that she would not be an authentic representation of a Wakandan. Furthermore, on a personal level, my sister were recently engaged in a discussion with another family member when my sister proceeded to ask me “do you admire light- skinned women?” The response that I loved ALL Black women and see them as goddesses resulted in an unexpected lengthy dialogue, and caused me to pause. Accordingly, this article will discuss the obvious lingering legacy of colorism through the eyes of a few of my sistas and will incorporate my own personal journey. Do lighter-skinned Black women view themselves the same way many of us darker- skinned Black women view them? What is their story?

Figure 2: Amandla Stenberg

Historical Context of Colorism

If you’re black, stay back;

if you’re brown, stick around;

if you’re yellow, you’re mellow;

if you’re white, you’re all right.”

This popular gem familiar to many African Americans summarizes the hierarchy that is stratified based on race and color. As such, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote in the early 1900s, “for the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line.” Du Bois (1903) was engaging the issues of race, racial domination and colorism a few decades after slavery had ended in the U.S. Despite Du Bois’ early discussion of the color line, it was however the Black, feminist writer Alice Walker in an essay in her 1983 book, In Search of our Mothers’ Gardens, who defined colorism as a preferential or prejudicial treatment of people of the same race based solely on their color. The history of colorism extends beyond these Black intellectuals and can be traced as far back as the Judeo-Christian story of the “Curse of Ham,” Genesis, 9 which provided a rationale for African enslavement by Christian, slave owners. Colorism further lengthened its fangs throughout European colonial and imperial history, and as such is prevalent in most countries throughout the modern world. In the United States, as in other countries directly impacted by the Atlantic Slave Trade, colorism has its roots in slavery as the ugly brother to racism. According to research (e.g., Russell, Wilson & Hall, 1993), while dark-skinned slaves toiled outdoors in the cotton fields, their light-skinned counterparts (sometimes siblings) worked indoors, completing domestic tasks that were far less physically grueling. The preferential treatment meted out to these lighter-skinned slaves was usually because they were often family members of the slave owners, product of the continuous raping of enslaved African women (Lake, 2003). Although slave owners did not recognize their mixed-race children as blood, they handed to them privileges that dark-skinned slaves did not enjoy. Accordingly, being light skin became an asset among slave communities. Less popular is the narrative of the suffering of those lighter- skinned slaves who experienced additional mis-treatment at the hands of their master’s wives and other relatives who knew of the blood relations. Like racism, after slavery ended in the United States, Latin America and the Caribbean, colorism lingered. Hill (2002) and Hunter (1998) have posited that in this day and age, colorism impacts Black women more than their male counterparts in regard to definitions of beauty and self-esteem.

My Story

In this journey to Nigrisescence – a development of my Black Identity (Cross, 1994) as an act of resistance and empowerment, mandated a self- love process that resulted in the wearing of my hair natural, little to no make-up and a general effort to love myself in all my Africanness. This would not be a revolutionary act at all, however, with a legacy of racism and a continuance of colorism, the very act of loving oneself as a black woman, a dark-skinned, natural/loced haired, curvy woman requires a revolution against the status quo. In this quest, the commitment has to uplift my sistas, especially dark- skinned, natural haired ones, ALL my sistas. Inherently, I believed that my lighter- skinned sistas had less of a challenge feeling beautiful as a result of receiving more media representation and a generally greater acceptance as conforming to a westernized notion of beauty. As a result, lighter-skinned Black women are more likely to be chosen as the token in movies, ads, videos, beauty contests etc. as representation of Black beauty. Despite having an awareness that my lighter- skinned sistas struggled as all Black woman do, I have never listened, REALLY listened to their unique struggles based on colorism. Until recently.

Figure 3: With My Sister. Photo Credit NLL

Sister, Sister- Different Shades of Beauty

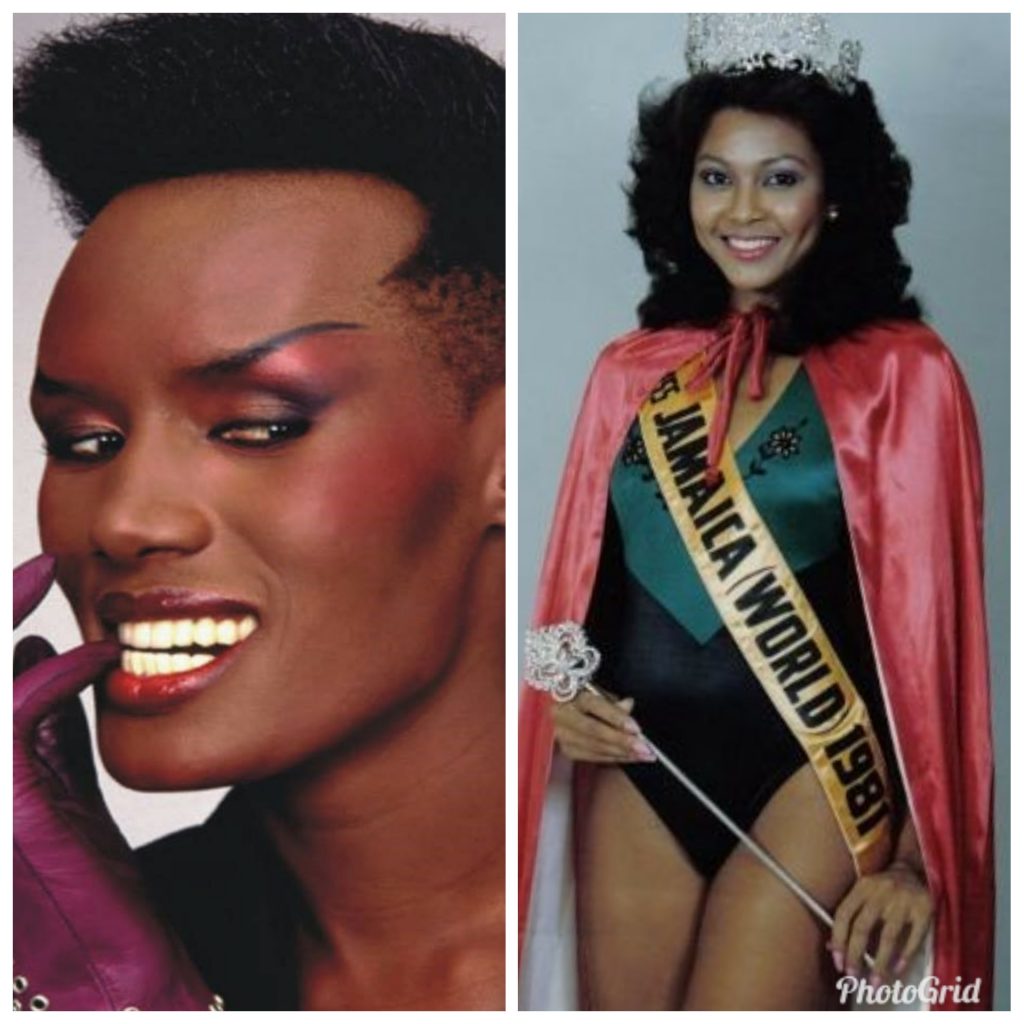

My sister is a light-skinned Black woman and, my late mother was a shade or two lighter than me. In my world, my sister and my mom were the epitome of beauty. They had the desired skin tone and the “pretty” hair that are considered standardly beautiful. As a result, I have always considered myself less beautiful than them. In fact, as a child, comparison to my Mom in not so positive ways regarding my beauty was a part of my socialization. Adulthood has afforded me a greater resemblance to Mom and that has translated into my feeling more beautiful. Similarly, with my sister, as teenagers, one of our hobbies was dressing up at nights and taking photographs. She would remark “I am the beauty queen and you are the model” and I would agree, but often wished that I could also be the beauty queen. In hindsight, this was a commentary on our Jamaican cultural beliefs and the dominant representation of beauty. It was and still is customary that lighter- skinned women would win the annual Ms. Jamaica beauty contests, while the darker- skinned women won the modeling competitions. Internalized issues of colorism had seeped into our subconscious and we applied it to ourselves without conscious effort.

Figure 4: Grace Jones,international model 70s & 80s and Sandra Cunningham, Ms.JA World, ‘81. Photo Credit Jamaica Gleaner

My sister has always been very beautiful to me, never giving thought that she could have had any issues with the color of her skin which I attributed directly to her looks. It has never been a topic of conversation between us, until recently. She expressed that she felt odd growing up as the only light- skinned family member. I was floored. We have been together for almost all our lives and her feelings and belief on this issue had escape me. Our conversation was taken a step further by asking a few of my lighter- skinned friends from Jamaica (Jamericans) in casual conversation about their thoughts and experiences on the issue of colorism. Among other questions, they were informally asked, “What has been your experience being of lighter hue in Jamaica and in the U.S.?”

Shared experiences

1.Muted Voices

Some lighter- skinned Black (Jamerican) women feel that their voices are further muted as there is the belief that because of their skin tones they do not experience as many issues as darker- skinned Black women.

- Black Woman Only

Many of my friends expressed a preference to identify as Black Women and do not wish to be further categorized into skin tones.

- Name Calling

Some light-skinned Jamaicans are called names such as “Mulatto, mongoose, red ants, red gal” by even family members and as such their self -esteem has been negatively impacted. The term “browning” is the most popular term used to call light- skinned women in Jamaica. Important to note that the concept of “browning” as popularized by D.J. Buju Banton connotes a positive description of lighter skinned Jamaican women, “Me love me car, Me love me bike, Me love me money and ting, But most of all, Me love me browning.” Buju faced a backlash based on the content of his song as he was accused of promoting a prejudice mindset and invalidating the beauty of dark- skinned Black women. As a response, he promptly released “Love Black Woman” which spoke of his love for dark-skinned women: “Mi nuh Stop cry, fi all black women, respect all the girls dem with dark complexion” as an attempt at an apology. Buju is a beloved reggae artist, however, many of us stayed “in our feelings” about his first choice of “Browning” over “Black woman.”

- Colorism within Families

The women, in my circle of friends also mentioned the role of family in either supporting or creating issues of colorism within their ranks. One woman described displays of racism and colorism in her family where they were discouraged from having intimate relations with anyone of darker hue.

Out of Many One People

Figure 5: Michael Manley and wife Beverley, 1972. Photo Credit-Jamaicans.com

Marinating in these comments, illuminated the reality that there is much dialogue needed in our own communities to further unpack this lingering issue of colonialism. Albeit, this conversation is not new. Historically there were considerable negative comments throughout the island nation when then Prime Minister of Jamaica, Michael Manley married a dark -skinned Beverley Manley (Fig. 4). In many circles it was rumored that Manley had married a poor, afro- centric dark- skinned woman to ingratiate himself to the poor, according to Mrs. Manley in “The Manley Memoirs.” Mrs. Manley also purported that as a young girl, she was starved of her mother’s affection because she was darker than her siblings and forced to do housework while her sisters relaxed, not an uncommon phenomenon in my own experience. To this day, in Jamaica a country with an overwhelming majority Black population, many black men (especially wealthy) actively seek out lighter-skinned women as potential partners. Parents sometimes treat their own children differently based on skin color, additionally general perceptions of intelligence, character and class are often defined amongst color lines and different grades of color, that is of Blackness. Nevertheless, based on the dialogue with some lighter-skinned Jamaican Black women, their experiences have included their own struggles with colorism which is often not part of the popular narrative. The idea of unearned benefits of being lighter that is believed by darker- skinned women seemed to rival the need to always having to explain their lighter shade, and, not fitting in at any end of the color spectrum. As Jamaicans would say “more pon plenty” that is what these conversations have revealed to me, that lighter-skinned women have additional baggage as Black women, often not discussed. Two of the women that were asked about colorism for this essay stated that their response to questions about their lighter hue was usually reciting Jamaica’s Motta of “Out of Many One People.” A phrase that attempts to explain the effects of colonialism on the diversity and shades of skin color among Jamaicans.

Figure 6: Davina Bennet- Ms. JA 2017. Photo Credit -Jamaica Gleaner

It appears that we are progressing and finally seen a dark- skinned, afro wearing Ms. Jamaica – Davina Bennett representing Jamaica (Fig.6) and being placed third in the international Ms. World competition. On the other hand, can we really claim progress, when as one of my friends mentioned, the use of bleaching cream is still so rampant to lighten the skin tone of both women and men throughout the island? Additionally, we have seen a record setting movie “Black Panther” that has a cast of predominantly dark-skinned actors. But what does this mean for our lighter skinned beauties and actors? my sister asked, feeling left out of the Wakandan story.

Moving Forward

The issues of colorism, like racism will continue to be with us for a very long time and will project forward into the 21st century. It behooves Black people, as we tackle each strand of an ugly legacy that pitted us against each other based on phenotype, to listen to each other’s plight and accordingly validate the feelings of each of our subgroups. My sister’s question doubting my admiration of light-skinned women reminded me that it was I, who thought (for most of my life) that being beautiful meant being a- light- skinned woman . Until progression in my own development of a stronger Black identity, the revolution then became uplifting my further marginalized sistas of darker hue. As I said to her “it is not mutually exclusive,” we can uplift darker- skinned sistas while still admiring the lighter-skinned ones. To which she retorted “I understand colorism and its impact, however, we cannot discount one group’s marginalization over one another.” I whole-heartedly agreed. Black women’s cocoon of confidence in their unique and collective beauty has been interrupted and injected with self-doubt. Am I light enough? Dark enough? Too light? Too dark? This venom has impacted the collective self-esteem of Black women throughout the world.

A Lutta Continua

The struggle continues as Black people listen to each other’s narratives and hold hands in acknowledgement and affirmation of a legacy designed to destroy, but instead we must use to unite and conquer. As one of my friends said “…For me being brown skinned is of no importance as I cannot help the mix of my ancestors, but I will not perpetuate that one shade is better than the other. I love the diversity of my blackness! I love our differences that’s what makes our race unique.” Black people are challenged to evolve to the stage where there is an understanding that beauty is not universally defined. It is in fact a fluid, man-made construct that changes over time, over regions, over cultures. With this fluidity in mind, who then decides who or what is beautiful? In some African countries, women with larger frames are idolized as beautiful, but in most of the western world, the smaller frame women are considered standardly more beautiful. Therefore, for Black women to assert a definition of self, control of OUR standards of beauty becomes a mandate. If Black women do not assert this power, a perpetual cycle of low self-esteem will continue, subscribing to alien definitions of beauty and feelings of deficiency. Black men too must evolve to support this revolution, like Buju said in his attempt at a redemption “wedah uno black or brown uno ah Buju right han.” The revolution continues as Black women seek to “emancipate ourselves from mental slavery” and affirm that we are our own magnificent shade of beauty and we defy YOUR expectations. We are not “pretty for a Black girl,” we are beautiful in all shades, as is the rainbow.

#MELANINGODDESSES #PRETTYPERIOD #OUROWNSHADEOFBEAUTY

References

Du Bois, W. E. B. (1903). The souls of black folk. New York: Vintage Books.

Cross, W.E., Jr., Parham, T.A., & Helms, J.E. (1991). The Stages of Black Identity Development: Nigrisescence models. In R. Jones (Ed.), Black Psychology (3rd. ed., pp. (319-338). San Francisco: Cobb and Hen.

Hill, M. (2002). Skin color and the perception of attractiveness among African Americans: Does gender make a difference? Social Psychology Quarterly, 65(1), 77-91.

Hunter, M. (1998). Colorstruck: Skin color stratification in the lives of African American women. Sociological Inquiry, 68, 517-535.

Lake, O. (2003). Blue veins and kinky hair: Naming and color consciousness in African America. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Manley, B. (2008). The Manley Memoirs. Ian Randle Publishers.

Russell, K., Wilson, M., & Hall, R. (1993). The color complex: The politics of skin color among African Americans. New York: Anchor Books.

Walker, A. (1983). In search of our mothers’ gardens. San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace, Janovich